The number of people who visited Grand Teton National Park last year and how much they spent both broke records.

A new report released by the National Park Service shows that the spending in 2016 went a lot farther than the park boundaries. It details the economic impact of national parks on local economies.

“It’s just a reminder of the effect the national park has on the local economies,” Teton Park spokesman Andrew White said. “And it’s not just the park staff — it’s a community effort.”

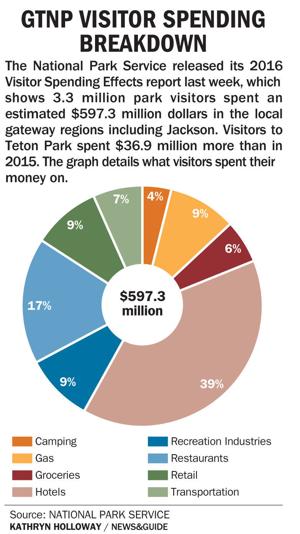

Grand Teton National Park’s 3.3 million visitors spent an estimated $597.3 million last year in local gateway communities. That number is up 6.6 percent from 2015.

“We definitely attribute that to the centennial,” White said, referring to the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service in 2016. “But it also seems to be part of a larger trend.”

Visitor spending and its ripple effects have increased steadily over the past five years.

The report tracks not only visitor spending but also the results of that visitor spending. It divides the numbers into direct and indirect effects of visitor spending. Visitors will spend money within the local community. The sales, income and jobs resulting from those purchases are the direct effects.

Indirect effects are from the additional jobs and economic activity supported when those businesses then purchase supplies and services from other local businesses. Employees using their income to purchase goods and other services in the regional economy contribute.

“It’s state of the art, but there are limitations,” White said of the way the data is crunched.

Part of the limitation is the gateway communities included. The report does not just include Jackson, but all counties within or intersecting a 60-mile radius around each park boundary.

“If you were to draw a circle around the park, it’s anything within that,” White said.

Because of Teton Park’s proximity to Yellowstone National Park that calls into question how much of the two parks’ data overlap. Nevertheless, data collection methods give pretty accurate results.

“There probably is some overlap,” he said, “but because we have good park-specific data, there isn’t too much.”

Yellowstone brought in a record-breaking 4.25 million visitors in 2016, but its spending was lower than Grand Teton’s visitors. Visitors spent $524.3 million in communities near Yellowstone, 11 percent less than Teton visitors.

White said that the big driver in the difference is hotel stays. He said that most people who visit Grand Teton stay outside the park, usually at hotels.

“The hotel rates for the gateway communities around GTNP are higher than those around Yellowstone,” he said.

People who stay outside the park are more likely to go out to eat than buy groceries, and spend money at retail outlets and on guided trips.

“When you add in those ripple effects, that’s really what’s driving the difference,” he said.

On a wider scale, 7.5 million visitors spent an estimated $945.3 million in gateway regions while visiting National Park Service units in Wyoming. That in turn supported 13,400 jobs, $392.1 million in labor income, $684.9 million in value added and $1.2 billion in economic output to the Wyoming economy.

Other parts of the Park Service in Wyoming include Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area, Devils Tower National Monument, Fort Laramie National Historic Site, Fossil Butte National Monument and the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway.

Nationally, visitors to 417 National Park Service units contributed $34.9 billion to the economy in 2016.

Not only does tourism in national parks contribute to the economy, it represents a huge return on public investment.

Every tax dollar that Congress spends on the National Park Service returns more than $10 to the national economy, White said. That high return is because visitor spending goes through local, state and the national economies.

“We’re here so people can enjoy this place, but we also like to support our local economy,” he said. “It’s an additional benefit.”

Contact Erika Dahlby at 732-5909 or [email protected].