Choosing the Right Fly Fishing Outfit

World Recreational Fishing Conference

August 1, 2017How Fish Behave During a Solar Eclipse

August 21, 2017Choosing the Right Fly Fishing Outfit

When choosing a new fly fishing setup, today’s angler is faced with a multitude of options, and the choices are enough to make a neophyte’s head spin. This article will explain the most important factors to consider when looking at different rods, reels, and fly lines, as well as how to match them together to create an outfit that meets each angler’s specific needs.

Understanding Fly Rod Length, Weight, Action, And Construction

A fly rod is arguably the most important tool a fly fisherman owns. Modern fly rod designs vary greatly depending on the intended use, so it is important to understand the mechanics and basic design characteristics of fly rods when selecting between the different options available.

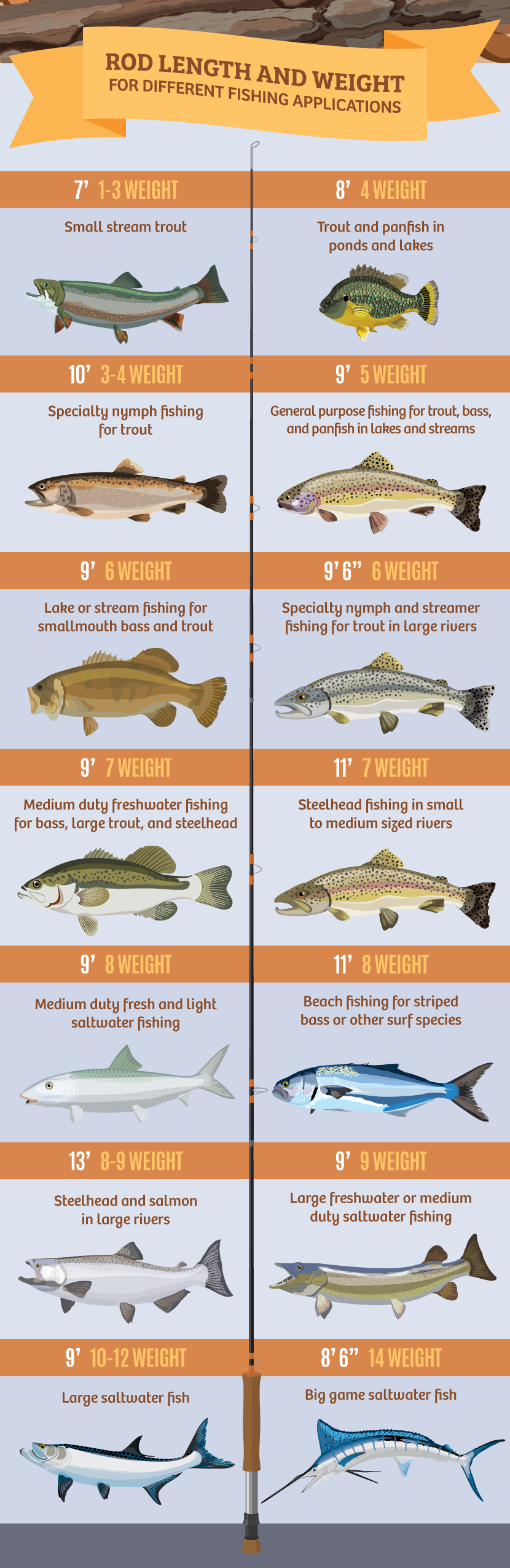

Length

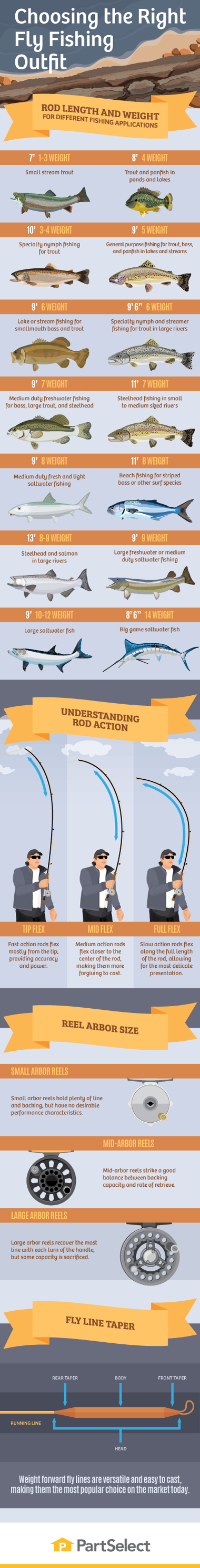

These days, manufacturers offer rods varying in length from as short as 6 feet to as long as 15 feet. In general, rods on either end of the length spectrum are meant for specific applications, while rods that fall in the center of the spectrum are more versatile. A 9-foot fly rod is considered standard length: with a 9-foot rod, an angler can cast effectively at most fishing distances and control the line on the water, making 9 feet a great choice for most anglers in common situations.

So why go shorter or longer? Shorter rods excel in casting accuracy and have greater leverage. Rods that are 6–8 feet are often sold in light weights for fishing small streams where casting room can be an issue. Also, some new heavyweight rod models are being manufactured in short lengths for casting big flies into tight spots and wrestling powerful fish out of their snaggy homes. These short, stout rods excel in targeting fish like largemouth bass, snook, and juvenile tarpon in areas where casting accuracy and leverage are important.

Rods longer than 9 feet offer the angler two distinct advantages: casting distance and line control. Rods in the category of 10–12 feet are becoming popular for anglers that specialize in nymph fishing for trout because the added length allows an angler to hold more line off the water, which aids in control and reduces unwanted drag. In addition to improving reach, more length helps with mending and line control, enabling an angler to present the fly effectively at greater distances. If distance is desired, a longer rod may be the perfect fit. Spey rods, or two-handed fly rods in the range of the 11–15 feet, are tailor made for casting and fishing at long distances. A two-handed rod in the hands of a skilled caster can easily deliver a fly at distances of 60 to more than 100 feet. Long, two-handed rods are popular for steelhead and salmon anglers who fish large rivers, and with beach anglers who need to cast far into the surf.

Weight

The spectrum of rod weights on the market today is almost as great as rod lengths, with models offered from as light as 0-weight to as heavy as 16. Almost every weight has a practical application, but fly anglers also have some general favorites. For example, the 9-foot, 5-weight is widely considered to be the most popular trout fishing fly rod in the world.

In general, fly rods of a certain weight are also manufactured in specific lengths to suit an intended purpose. A quick glance at the inventory at a local fly shop will show that most lightweight rods in the 0–3 weight range are manufactured in shorter lengths. This is because they are mostly used for small stream or pond fishing, where shorter length is an advantage and the fish are generally small. Rods in the 4–8 weight category can come in more varied lengths, and comprise the bulk of what most freshwater anglers need for targeting a variety of fish species. Weights 4, 5, and 6 are the most popular sizes for targeting trout, while heavier weights are used for targeting larger fish or casting large, heavy flies. Rods in the 9–16 weight category are generally only used for very large freshwater fish or saltwater applications, with the 12–16 weights being designed specifically for big game species such as tarpon, giant trevally, sailfish, and tuna.

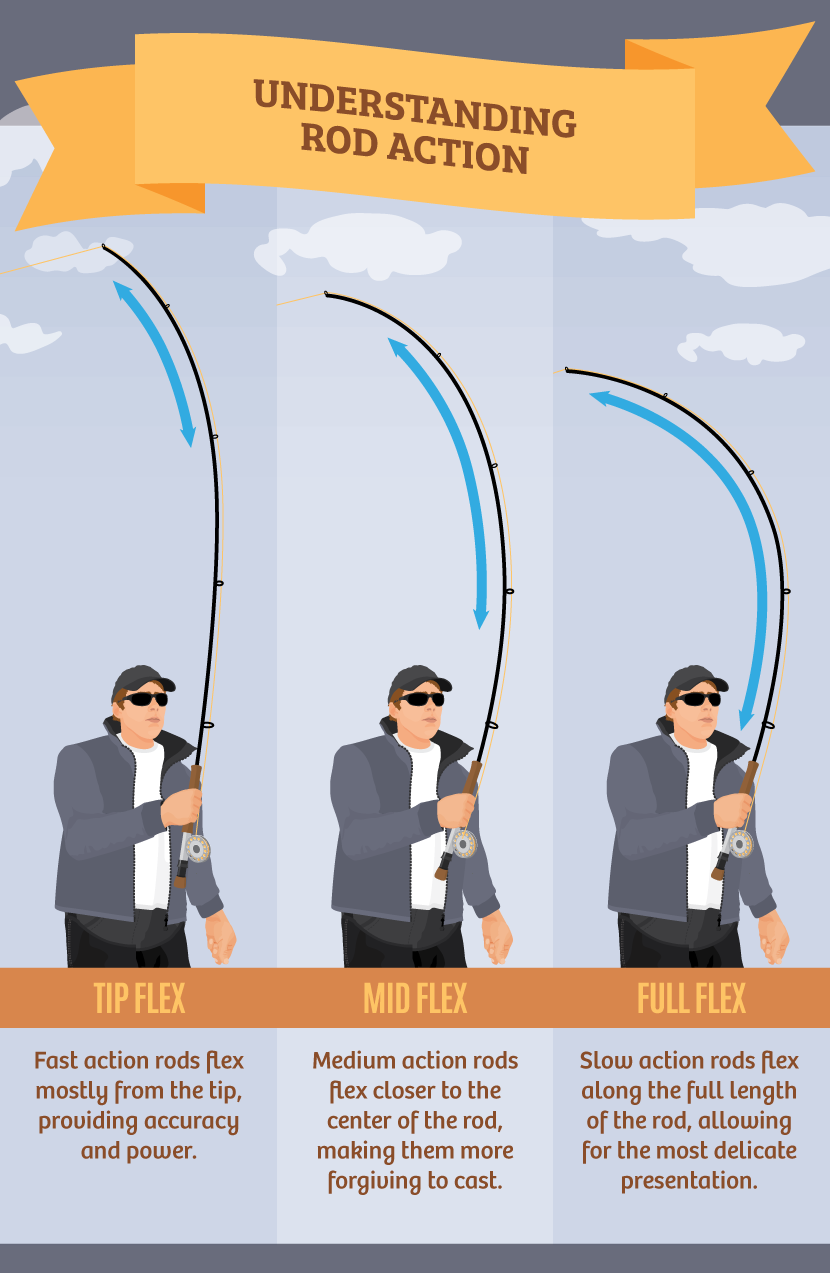

Action

Rod action has to do with how the rod flexes under the weight of the line during the casting stroke, and then how it transfers that energy into the line to create the cast. Most fly rods on the market fall into 1 of 3 categories: fast, medium, or slow. This categorization has to do with how fully the rod bends when placed under a load, and how quickly the rod recovers to a straight position when the load is released.

Fast Action

Fast-action rods flex mostly in the top third of the rod when placed under a load, and they recover quickly when the load is released. The lower portion of the rod is stiff and powerful, while the tip is supple and flexible, allowing for precision casting, line control, and distance. Fast-action fly rods are popular for their high-performance characteristics, but these same strengths can make them difficult to handle for beginning fly anglers.

Medium Action

Medium-action rods flex from the top half of the fly rod and recover more slowly than fast-action rods. The general feel is similar to that of a fast-action rod, but the additional flex makes them smoother and more forgiving to cast. Medium-action rods are great general purpose tools and are easier for most beginner to intermediate fly anglers. Advanced casters will still appreciate their deeper flex characteristics for specific applications.

Slow Action

Slow-action fly rods feature the fullest flex, bending deep into the butt when placed under a load and recovering slowly when the load is removed. This flex profile is valued for creating a soft, delicate presentation or when the angler needs the rod to load up and cast a very short amount of line, such as when fishing in a brushy creek. Slow-action rods are mainly used for specific purposes, and represent a small subset of fly rods and actions on the market.

Rod Construction

The three main construction materials used in fly rod manufacturing are graphite, fiberglass, and bamboo. Each one is appreciated for its own performance characteristics and distinct feel.

Graphite is the most popular and widely used material used for fly rod construction. The material is lightweight, sensitive, flexible, and incredibly strong. Manufacturers can apply graphite in different layups and tapers when building rod blanks to achieve almost any desired action or feel, making graphite an incredibly versatile material for fly rod building. The lightest, strongest, and highest performance fly rods on the market are made of graphite. The only real disadvantage is that graphite fibers can be brittle and a bit fragile. Finished fly rods are protected by a layer of epoxy resin, but anglers still need to take care when fishing and storing their rods.

Fiberglass was replaced by graphite in the 1980s as the material of choice for fly rod construction, but its distinct feel and durability keep it relevant. Fiberglass fly rods are still offered by many of the top rod manufacturers. While it is a bit heavier and less sensitive than graphite, fiberglass is flexible and durable. Most fiberglass rods in shops these days are offered in slow-action, full-flex profiles and in lighter weights from 1–5. In general, they are meant for small streams and lakes where anglers are targeting small- to medium-sized fish. However, a few anglers have discovered that the incredible strength and flexibility of fiberglass is an advantage when targeting large powerful fish, and are using rods in the category of 8–12 weight to fight and land some impressive specimens.

Bamboo has withstood the test of time as one of the best natural materials for fly rod construction. While it has been replaced by stronger and lighter modern materials, it still has its place in fly fishing. Bamboo has a natural full flex and a wonderful feel, and it is prized by anglers who appreciate the lively feel when casting and fighting a fish on a bamboo rod. It is not for everyone, or everything, and anglers looking for a general purpose rod or a first fly rod might want to look elsewhere. But, for those who are looking for a rod with a truly unique feel, one that makes it a joy to fish, bamboo may be the answer.

What Makes a Good Reel?

Fly fishing reels come in various shapes and constructions. Some designs are purely aesthetic, while some serve important functions. This guide will help you understand the most important aspects to consider when choosing a reel to match a fly rod.

Construction Material

Quality fly reels are typically made of aluminum, but not all are created equal. A high-end reel will be machined from solid bar stock aluminum and finished with an anodizing process, protecting it from scratches and corrosion. Less expensive reels are often die cast from aluminum alloys, and are more prone to bending or breaking if dropped. Spending a little extra to get a machined aluminum reel will pay off in the long run.

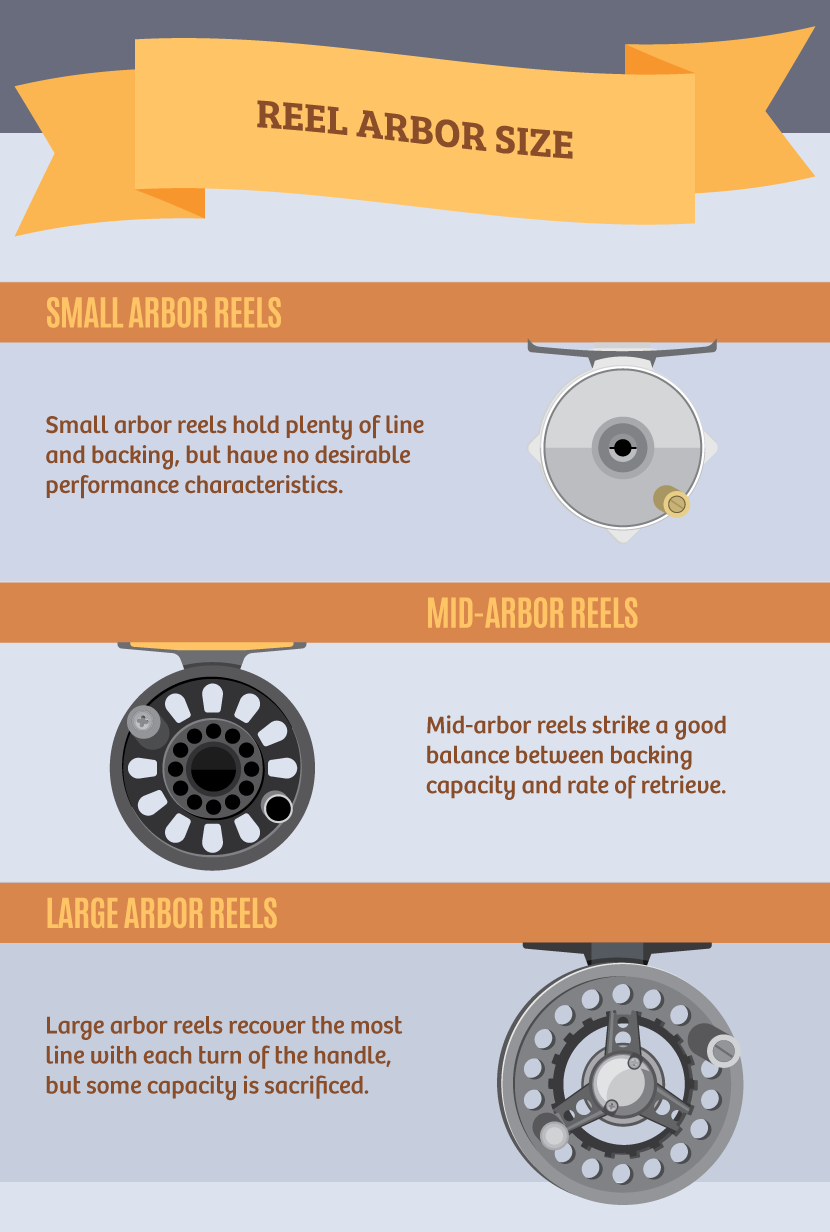

Arbor Size

The arbor is a term fly fishers use to describe the diameter of the inside of the reel spool. A reel with a small diameter spool is referred to as a small arbor, while a reel with a large diameter spool is said to have a large arbor. Also, many options are on the market that fall somewhere in the middle, called mid-arbor reels. Large-arbor reels were originally developed by big-game fly anglers who needed to be able to retrieve line quickly while fighting large, fast-moving fish. The large-arbor design has the added advantage of holding the fly line in looser coils, so it is not as prone to tangling while fishing.

Drag

Drag is perhaps the most important performance characteristic on modern fly reels. Drag mechanisms range from click-pawl, which is simply a gear that clicks against a metal spring, to fully sealed, fully adjustable carbon fiber disc systems. A smooth drag system is an important consideration when fishing with extremely light tippets or whenever large, powerful fish are the targeted quarry. In contrast, an angler fishing small streams for trout that seldom get above 10 inches may never even use a drag. Saltwater anglers will appreciate having a sealed drag system.

When choosing a reel, consider the weight of the fly rod and the intended use. Most manufacturers label their reels with the suggested matching line weight, and this can be a good starting guide to help you pick the right size.

Matching The Right Line to Your Rod

Having the right fly line can mean the difference between a successful day and a very frustrating experience on the water. It is not only important to match the correct weight fly line to your rod, but to also choose the correct taper and sink rate. These days, many options are on the market, and it can get a bit confusing. This guide will help you understand the basics so that you can choose the best option for the fishing you will be doing.

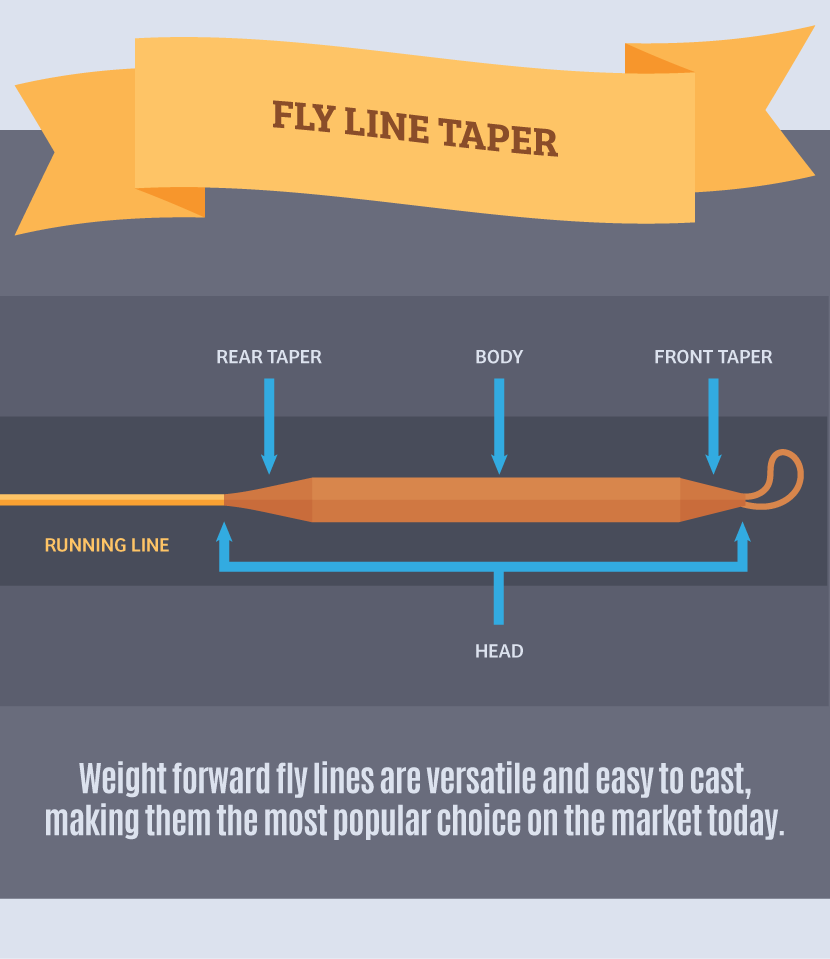

Taper

All fly lines have a taper, meaning if the fly line was stretched from end to end, the thickness would not be uniform. Instead, the mass in the fly line is distributed where it is needed most for specific casting characteristics. Although a variety of line tapers are available on the market today, most are simply variations of the basic weight-forward taper. This taper design places most of the mass in the first 30–50 feet of the line, at the distance where most anglers are comfortable casting and fishing. The remainder of the line is thin and level, which makes it perfect for shooting line, should an angler need to reach a greater distance. The weight-forward taper is by far the most versatile and popular taper design, and should be your first choice when looking for a new fly line.

Density

Fly lines come in floating, sinking-tip, and full-sinking variations. Your line choice should be dictated by where you want to deliver your fly in the water column.

Floating

Floating fly lines are the most common, and often the best choice for general purpose angling. They are appropriate for delivering a fly anywhere between the surface and around 6 feet deep. Any deeper, and a sinking or sink-tip line would be a better choice. And, don’t make the mistake of thinking you need a sinking line to fish nymphs or other subsurface flies: a floating line coupled with a long leader and a weighted fly is a common and deadly tactic for delivering a fly below the surface.

Sink Tip

Sink-tip lines are effective for delivering a fly from just below the surface to around 10 feet deep. A sink-tip line is a floating line that transitions into a sinking tip in the last 8–15 feet of the fly line. Because the back end still floats, they are easier than full-sinking lines to pick up off the water when making a new cast. The floating rear end also helps anglers make mends and adjustments when drifting a fly in current. Sink tips come in different sink rates that are measured in inches per second. A low sink rate would be considered 1–2 inches per second, while 8–10 inches per second is about as fast as you will find.

Full Sinking

Full-sinking lines are used when an angler needs to keep the fly below the surface at a sustained depth throughout the retrieve, or when the fly needs to be delivered at extreme depths up to 20-plus feet. Like sink-tip fly lines, full-sinking lines are offered in multiple sink rates. The sink rate is chosen based on how deep the fly needs to be throughout the retrieve. An intermediate fly line that sinks at 1–2 inches per second is a good choice for presenting a fly in the top 2 feet of the water column. A medium sink rate from 3–5 inches per second is a good general purpose choice. For achieving extreme depths or keeping a fly below the surface in heavy current, a fast sink rate of 8–10 inches per second is appropriate. With any sink rate, the longer one waits after the cast before retrieving the fly, the deeper it will go. Full-sinking lines are popular with stillwater and saltwater fishermen who often use subsurface presentations to target deep holding fish.

How to Choose The Best Outfit For You

When choosing a new fly fishing outfit, it is important to consider where you will be fishing, the species you will be targeting, and the methods you will be using. These three considerations will largely determine the length, weight, and action of the fly rod as well as the reel and line that will be matched. Here are some general suggestions based on experience, but the options are limitless when tailored specifically to your individual needs.

General Purpose For Small- to Medium-sized Fish

A 9-foot, 5-weight, medium-action fly rod coupled with a mid-arbor reel with a disc drag system and a floating, weight-forward fly rod is a perfect choice for general purpose freshwater fishing. The 9-foot, 5-weight can handle trout of all sizes and many warmwater species such as panfish and bass. The floating fly line will be best suited for fishing in streams, lakes, and ponds on or near the surface where anglers are most likely to encounter fish.

Small Stream Fishing

A 7- to 8-foot, 2- to 4-weight, slow- to medium-action fly rod coupled with a small, lightweight aluminum reel and a weight-forward floating line to match the rod is a great choice for small streams and mountain lakes. In many such places, the biggest challenge is finding room to cast, giving the shorter length an advantage over longer rods. A lighter weight, full-flexing fly rod will load up better in close quarters when you might only be casting with 5–10 feet of fly line, and will be more sporting when fighting smaller fish.

General Purpose For Larger Fish

A 9-foot, 7- to 9-weight, fast-action fly rod coupled with a large-arbor disc drag reel and a weight-forward, floating line is a good general purpose choice for larger fish. The heavier weight, fast-action rod will provide the casting power and leverage to fish with larger flies and fight bigger fish. A large arbor reel with a good disc drag will provide fast line pickup and smooth fish stopping power during the fight. The weight-forward line is still the best all-around choice, but anglers fishing in specific situations may want to look at sink-tip or full-sinking options.